Known as the "villa of the liberty Peticia," the Staranzano villa was one of the residences with a residential and productive character in the territory that in ancient times was administered by Aquileia.

It was located along the Roman road from Aquileia to Tergeste (Trieste) and in the vicinity of a waterway, perhaps a branch of the Isonzo River that has now disappeared.

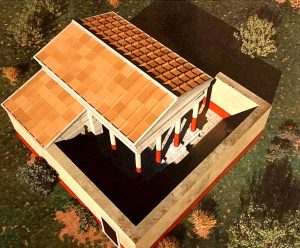

Like other "ville rustiches" of the Roman period, the villa gravitated to a landed estate (fundus) where various economic activities took place. à economic activities, from which the owner and his family drew sustenance and products to market. These complexes consisted of a residential part (pars urbana) and a purely productive part (pars rustica).

The Staranzano villa was discovered accidentally in 1955 on land owned by the parish church during work to modernize the sewage system. Archaeological excavations, conducted by Valnea Scrinari on behalf of the Venetian Superintendence of Antiquities, brought to light only the southeastern corner of the building, at a depth of about 80 cm from ground level and covering an area of about 130 square meters. From these early investigations remain the notes and sketches that Giovanni Battista Brusin, archaeologist and director of the Archaeological Museum of Aquileia from 1922 to 1952, recorded in his diaries. Other limited surveys and restoration and conservation work on the structures were carried out in 2002 and 2008 by the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici del Friuli Venezia Giulia.

The size of the villa is currently unknown.

Recent geoarchaeological investigations carried out in 2022 as part of the "E-VILLAE" project promoted by the Municipality of Staranzano have identified, to the southeast of the already excavated complex, traces of at least two rooms probably pertaining to the villa but not physically connected to the residential part.

The first building of the complex is dated to the second half of the 1st century BC. Based on archaeological data, we know that between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD changes were made to the building during at least two phases of renovation. The villa was inhabited until the beginning of the 3rd century AD. The renovations involved not only changes in the size of the rooms but also the use of different building materials in the masonry: the earliest phase saw the use of river pebbles, while in more recent ones brick fragments and tiles were also used. The latter were often stamped with trademarks referring to well-known local manufacturers.

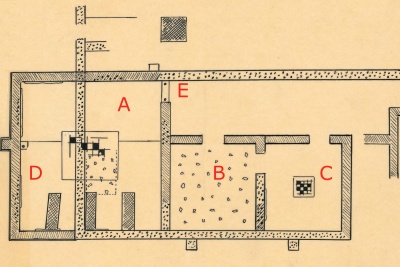

The 1955 excavation uncovered three identical rooms, paved in opus caementicium (beaten mortar encompassing flakes of stones of different colors), placed side by side and facing a long and narrow room, perhaps a courtyard, referable to the first building phase.

Durante la prima ristrutturazione l’ambiente a sud-est (A) fu notevolmente ampliato: una parte venne pavimentata in cubetti di cotto e l’altra in tessellato bianco e nero; al centro della sala venne inserito un mosaico a scacchiera bianco e nero (emblem). This room was perhaps used as a triclinium (dining room), with the triclinar beds probably arranged on the terracotta-paved area.

Anche l’ambiente più a nord (C), oggi coperto da una tettoia, fu ripavimentato con un mosaico a tessere bianche incorniciato da una fascia a tessere nere. Al centro del pavimento venne inserito un riquadro con motivo a scacchiera in bianco e nero, anch’esso delimitato da una cornice nera.

The last renovation,characterized by a sloppy construction technique,made significant changes to the great hall (A). Part of it was subdivided into four small rooms or cells by means of low walls. The discovery of a squared stone block with a central hole (D), juxtaposed to the perimeter wall of the house at an external buttress, leads to the hypothesis that a post was inserted there to support a movable partition (e.g., a curtain): this would have allowed the room to be further divided, creating a kind of antechamber and preventing the view of the small cells.

Such elements suggest the transformation of this part of the villa into a sacellum, That is, a place intended for domestic worship. The room was entered from the courtyard through a door documented by the finding of a stone threshold (E) with hinge holes. This transformation into a sacellum is corroborated by the finding, in this room, of a large stone slab (dimensions preserved 57 x 57 cm), perhaps a canteen, a kind of table for ritual offerings.

It bears the engraved inscription B(onae) D(eae) V(otum) / PETICIA L(uci) L(iberta) AR[-] testifying to the dissolution of a vow made by Peticia, freedom (freed slave) of the family of the Peticiiat Bona Dea.The inscription is datedat the end of the first century B.C. and the first half of the first century A.D. and thus testifies that the cult to the Bona Dea was practiced in the Staranzano villa already during its first phase of planting.

A large quadrangular platform was also found in the inner courtyard of the complex, paved with terracotta cubes, whose function or possible relationship to the sacellum is unknown.

The worship of Bona Dea was particularly widespread in the Aquileia area and was connoted as a mystery cult, practiced only by women, whose characters could not be known to men. Celebrations were held in public form in temples but also in private form inside homes; free women and enfranchised slaves participated.

La presenza delle piccole celle nell’ambiente A della villa riporta a edifici sacri dedicati a questa divinità salutifera, ad esempio al tempio di Bona Dea Subsaxana on the Aventine Hill in Rome or the one identified in central Trieste in 1910, where the cells were perhaps intended for the performance of divination activities or healing rites.

Understanding the architectural features of the Staranzano villa and reconstructing its phases of occupation are particularly problematic because of the paucity of everyday materials recovered during archaeological investigations, such as pottery and amphorae. Only stamped tiles and a few metal objects, such as a bronze net needle, are mentioned in the 1955 excavation diaries.